(I wrote this essay about 12 years ago for The Surfers’ Journal, focusing on the act and journey of a surfboard shaper building a surfboard for someone that means a great deal to one. Flippy Hoffman, on whom this story is centered, got his hackles up over my original title and we ended up running with The Shaper’s Fugue, which I always hated and felt undermined the whole story from the outset. Since the present surfboard climate is favoring the small builder again, I have decided to re-run the piece here since there is lots of how-to information for the backyard builder….)

Shaping a surfboard is like taking a drive over a long and familiar road. Over the years the shaper develops an ability that allows him, like the skillful driver, to slip into a trancelike state in which he rolls along on autopilot. In shaping, each step leads to the next, and after thousands of boards the discipline of a deeply-grooved routine frees the mind to roam. And while the road leads to the same destination, the view continually changes. For me, the act of shaping a surfboard becomes a travelogue – I like to look out the window as I work. When carving out a surfboard for a friend, the road meanders past many memories. Lost in music and the cool dark room, the hands fly over the blank of their own accord while the mind sweeps over the years of friendship, here and there slowing to review the good times, the frustrating contradictions, an argument, a shared joy.

Flippy Hoffman needed a new surfboard. That summer I had gone with Flippy on a diving trip to one of the Channel Islands. There were four of us: Flippy, Matthew Barker, and my wife Claudia and I. When talk turned to surfboards – as it invariably does with a crew of surfers – Flippy grumbled about not being able to find a big board that suited him. Swaying at anchor in a calm bay, we sketched out length and rocker and blank selection. As we laid the imaginary keel, we agreed that bottom rocker would be critical. Matthew and I raked through our mental catalog of rockers and blanks, but nothing seemed to fit. Finally, Matthew, who has worked at Clark Foam for 23 years, volunteered to go out into the glue shop and bend the rocker by eye. Then the conversation wandered into fish and boats and jet skis, and we forgot all about the board.

Back home a week later, a letter came from Flippy. I tore open the envelope and pulled out a plain white napkin, soiled with mustard from his lunch-break. Baffled, I unfolded the napkin. Inside was a check, made out for double my normal fee. Scrawled on the napkin was, “Go, Go,GO!!”

The balloon had gone up!

A few days later I pulled up to my shaping room in San Luis Obispo to find an enormous blank leaning against the garage. Below the neatly stenciled labeling of length, rocker and stringer was chalked “Operation Megalodon” – Matthew’s code name for the Flippy project. I got out of the truck, lugged the blank inside, set it on the racks, and flipped on the light switch. The twin banks of fluorescent bulbs flickered and hissed, and the room glowed in blue undersea light. I stepped back to study the bottom curve, eyes following the stringer as it soared from nose to tail. Intending to build an 11-foot surfboard around this rocker, I felt some anxiety over whether I would be able to meld it seamlessly into the outline, widepoint, and thickness distribution. But Matthew had done well: here was a clean and unique bottom rocker to build on.

After breakfast the next morning I was ready to begin. Summer days in San Luis Obispo grow hot by noon, so I like to rough out a few boards in the morning and finish them in the cool of the evening. I switched on the lights and air compressor, and pinned the order sheet and a snapshot of Flippy on his boat onto my bulletin board.

I often make notes for stories while I shape. This time, I thought it would be interesting to keep a record of impressions and memories driven to the surface while immersed in the process of building a surfboard for a friend. I cleared a space on the bulletin board and tacked on it a writing tablet. Then I wrote, “11’3” Superlight, off-label use, fresh glue…”

The blank lay on the racks, crowding the small converted garage, and smelling of freshly sawn wood and curing glue. The 11’3”… Ah, my old nemesis! George Downing and Dale Velzy had shaped the plug for the 11’3” 15 years earlier, and they crammed plenty of foam into it. If you don’t get the rocker just right you’ll oftentimes run into a strange kink running through the belly. You don’t want to mess around with this blank – like a charging tiger you want to nail it with the first shot or it will bound, wounded, into the underbrush, and you’ll have to crawl into the thicket and deal with it. Still, it’s a very versatile blank, and over the years I’ve come to embrace it with a certain grudging fondness.

Yet, this time I faced the 11’3” with a light heart; all I had to do was keep the outline and thickness distribution tied to the bottom curve – it seemed unlikely I would wander into the thicket.

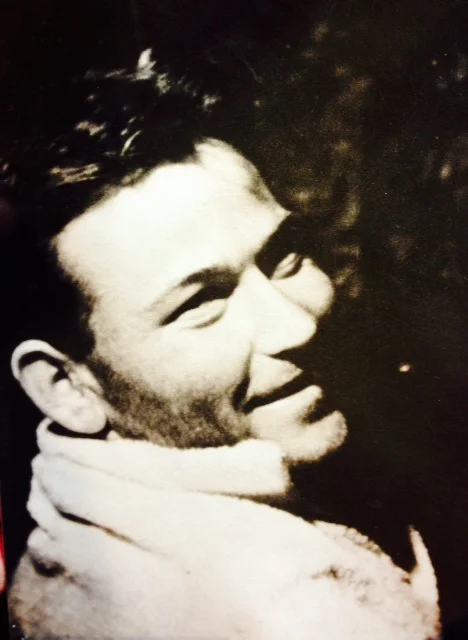

Searching for a new pencil, I glanced at the photo of Flippy on his boat. He was standing near the stern, one hand on his hip, impatient. His thick diving wetsuit hung from the bimini top, waiting for the next dive. Flippy Hoffman had spent much of his life underwater – years of it if you totaled it all up – whether driven there under the fist of a huge wave or goaded by his pursuit of abalone. He was part of the diaspora of Californian surfers that swept into Hawaii in the early 1950s, in the original crew of big wave hunters that pushed out into larger and larger surf until the limits of lungs and equipment fought them to a stalemate on the 38th parallel. While many of his compatriots financed their winter pilgrimages to Hawaii by lifeguarding in the summer, Flippy chose instead to make his living as an abalone diver. For years, he dove all along California, including a spell along the treacherous coast between Morro Bay and Big Sur. Twice he was stricken with the ‘bends’, once so severely that the Navy commandeered him for a study – they wanted to know why he was alive. In the mid-‘70s Flippy and a few friends quietly and without fanfare surfed Kaena Point, “just for the helluvit.” He rode a 15’5” full-race gun out in the giant North Shore cloudbreaks, a giant red missile with the battle cry ‘AH-WOOooo!’ painted on the deck. He promised three dollars to any gremmie who returned the board after finding it washed ashore or floating in the rip. “This is how human beings behave,” George Orwell once wrote, summing up the fierce individualism of western Americans, “when they are not frightened of the sack.” Now in his 70s, Flippy was content to run his 39-foot twin-hulled time machine out to the offshore islands, diving and surfing and sharing the sunsets with any of his friends that happened to anchor close by.

I found a pencil and fed it into the sharpener. My favorite part of building a new surfboard is laying out its outline. Not only does this task incur the least dust of the entire process, but also in templating you have a chance to create an original design, since most production shapers nowadays work from a handful of close-tolerance blanks with very similar rockers and foils.

I stretched the measuring tape along the bottom from nose to tail, marking off the points used to set the widths of nose, center, and tail.

Remember those beautiful Brewer ‘Pipeliner’ longboard guns of the mid`60s?

My plan was to take the outline from that classic model, then modernize it with everything I had learned from making surfboards for the big board crew at Makaha. Watching Buffalo Keaulana effortlessly swing through turns on his 11 and 12-foot boards had shattered, for me, all former ideas concerning the performance envelope of long and thick surfboards.

I placed the pencil dots: 15” nose, 23.75” width (widepoint 11” up from center), 13.25” tail. Rummaging through the pile of templates, I finally selected an enormous spin template taken from a vintage 11’6” Brewer ‘Pipeliner’. I laid the masonite on the blank, adjusting its curve up and down to find a fit. Something about shifting the template so that it notched all three dots reminded me of Flippy ‘backing and filling’ his boat into the tiny doghole inlet next to his secret spot. We had spent an afternoon surfing there, just three of us out at a rock pile somewhere along an offshore island. The waves were small and sluggish, but the water was cool and clear. The eel grass tickled our feet as we waited for sets, and garibaldi fluttered over the reef like golden butterflies. Flippy sat on the boat, anchored scarcely twenty yards from us, reading a magazine. Hunched in his chair on the stern, chin to his chest, synchilla beanie pulled down over his forehead, he grumbled as he tore through a dog-eared copy of U.S. News and World Report. He looked up when one of us caught a wave, nodding and smiling grimly, before returning to the villainous world of high finance.

He finished the magazine, stood up, and began stumping impatiently around the deck. Matthew, who had been on many Flippy excursions, paddled back out after a wave and said, “I think Flippy wants to get a move on to the next place. We better go in.”

We paddled back to the boat. Flippy lowered a hinged section of gunwale abaft, customized for solo diving, and stood over us as we climbed aboard. He looked down with envy at our short, thin surfboards fanning out from their tether on the stern cleat.

“Goddammit!” he exclaimed, “I’d give anything to be able to stand up that fast!”

“Well, you really don’t have a choice with these boards,” I replied somewhat diplomatically.

Matthew explained that Flippy, at 72 years old, had a hard time standing up quickly. To compensate, he rode an enormous board.

“…But by the time I get up,” growled Flippy, “the damned thing’s already burying the nose.”

Matthew whispered to me, describing the board as a mulish tub of flotation.

“You know, Flippy, I’ll bet we can lick that problem,” I said, thinking of Buffalo sweeping out of a deep fade on his 12-footer. “With a better rocker, you can pile on all the thickness you want, and take all the time you need standing up.”

“That’s great! You go right ahead. Grubby owes me a blank, anyway. Just work it out with Matthew.”

Operation Megalodon had begun.

It took about 45 minutes to get the outline right. The rich black lines of the Berol drafting pencil blossomed and climbed, only to be blown off and scrubbed away a dozen times. Finally I had a baseline curve that looked right. Then, I pulled out two newer templates and grafted a cleaner, more modern nose and tail curve onto the fuselage of the old 11’6”. Any board of Flippy Hoffman’s, I knew, would be scrutinized by Phil Edwards and Mickey Munoz. Phil and Mickey not only shape beautiful surfboards, but also design and build lovely power and sail craft – you had better believe they both have an uncompromising eye for clean lines.

I took the blank outside and stood it up against the house. Like a sea captain rowing out to check the trim of his warship, I stepped back and appraised the outline, feeling as if Phil Edwards was looking over my shoulder.

I usually trust the first glance at a freshly drawn outline. I have found that if you look too long you’ll start imagining kinks and bumps, or be tricked by the interference of surrounding lines and shapes. It takes a long time for the apprentice shaper to translate in his mind the simple penciled curve into a complex three-dimensional foil.

Satisfied with the outline, I took the board back inside and with a handsaw began cutting along the outline from tail to nose. The thick white beams of waste foam peeled from the emerging shape and sagged to the floor. Certain steps in the shaping process conjure in my mind a distinct image or memory, probably stemming from the intense concentration required when I was learning my craft. Each time I cut out a new surfboard, for instance, the same loop of mental film pops into my head: I envision a group of 1950s surfers holding down a balsa blank on a pair of sawhorses, while a guy in dungarees stands atop it, sawing along the rail line with a massive ripsaw. Perhaps this is why I prefer to use a handsaw rather than a power saw or router. I enjoy the sense of a connection to the past, of being a link in a long chain of surfboard builders that stretches all the way back to stone adzes and the virginkoa forests of Hawaii. I know a surf journalist who, valuing performance over aesthetics in all matters pertaining to surfing, would say that I am a sad victim of what he calls ‘Failed Romanticism.’ Yes, yes, all very modern and all that. …Nonetheless, every time I cut into a fresh blank I feel that I am sharing in the discoveries made in those exciting early years of the modern surfing era, when it was possible for any surfer, with each stroke of the ripsaw and pull of the drawknife, to liberate from a rough balsa slab the ability to angle tighter, to ride deeper, to extend control into bigger and bigger waves.

One of my favorite writers, Nevil Shute, an aviation engineer who wrote novels in his spare time, spoke of the halcyon days of aviation, remarking that “for about thirty years there was a period when aeroplanes would fly when you wanted them to but there were still fresh things to be learned on every flight, a period when aeroplanes were small and easily built so that experiments were cheap and new designs could fly within six months of the first glimmer in the mind of the designer.”

My life’s work as a surfboard designer is founded on the belief that, in spite of all the escalating threats to hand-shaped custom surfboards, we are all still shaping and surfing in such a halcyon period. But, like Shute, I worry that false worship of glittery new technology could strip away from surfboard manufacture the importance of shape and design, casting us into the same situation as post-World War II aviation, when, as Shute wrote, ‘aeroplanes had grown too costly and complicated for individuals to build or even operate.’

After cutting out the shape and sanding it true, I donned goggles and headset and picked up the power planer. The familiar growl of the Skil 100 filled the room as its newly sharpened blades chewed long strips of foam from the blank. Walking the planer back and forth over the bottom, I felt the curve begin to come to life beneath the skid, sensing through its rise and fall the flat belly, the sharp vee panels, the sweep of the entry rocker as it raced into the nose.

The bottom completed, I turned the board over and set to scraping only the crust from the deck, turning the planer sideways and using only the corner of its shallowest cut. Flippy’s board would spend much of its life aboard his boat. Sea-going surfboards tend to take a lot of abuse, so I wanted to keep intact as much of the denser deck foam as possible.

He had also told me that he would be riding the board at Poche and Cabo San Lucas, but probably wouldn’t take it to the North Shore. Nowadays he mainly rode his jet ski there, heading out alone into the cloudbreaks off Avalanche, his old stomping grounds. There, he skated over the acres of giant peaks, outrunning clean-up sets and screaming into dozens of waves, waves that had once taken him hours to line-up a single ride. One day he was knocked off his ski in 15-18-foot surf at Avalanche. The ski disappeared, dragged toward shore by the relentless walls of soup. Flippy put his head down and headed for shore, figuring on nothing more than yet another long and boring swim. Halfway in, he heard the peal of sirens and spotted a phalanx of emergency vehicles streaming along the beach road at Hale’iwa. Must be someone caught in the rip at Ali’i Beach Park, he thought. Greenhorns! He had nearly reached his capsized, swamped jet ski when he saw the massing crowd of rescuers pointing at him.

Flippy was furious.

“Jesus!” he said afterwards, “A man can’t even fall off his horse nowadays without some busybody calling the fire department. Ri-dic-ulous!”

Hearing him say things like that, I couldn’t help but recognize the similarities of speech he shares with Buzzy Trent – and both of them their mentor, Bob Simmons. In the early ‘50s the two young surfers shared a shack in Makaha with the brilliant board designer, and I imagine I can hear the distant echo of Simmons each time Flippy exclaims ‘fan- dam – tastic!”

Now the blank was milled to the desired thickness. After a few minutes spent foiling the tips and adjusting the flow of thickness to the widepoint, it was time to fine-tune the arc of the stringer. There is a certain joy in running a sharp block plane over a cedar stringer, in how the soft soapy wood peels from the blade in tight, sweet-smelling curls. All the stringer woods have their own scent: basswood with its aroma of roasted coffee, spruce with its astringent piney smell, redwood with its rich, syrupy tang of an old barn.

I cleaned the bottom up with a Surform, finally scraping the apex of the vee into its proper position beneath the fin area. I’ve been using a Surform since the 7th grade, first on homemade skateboards and then on my first surfboard shaped out of a stripped-down longboard. Surforms hold for me a peculiar nostalgia, like coconut-scented Winter Wax and the smell of polishing compound on a freshly-rubbed out surfboard. I can’t resist an old Surform I come across at a swap meet or antique store – the hefty steel ones made in the ‘50s hold for me the same magic as brand new Keds and whirling pushmowers do for Ray Bradbury.

I sanded the bottom flat, using a worn sheet of 40-grit wrapped around a balsa block, and working toward the tail. There, I gently feathered the flat into a slight roll, and the roll into the sharper panels of the vee.

The bottom contours set, I placed a weight on the blank and began to Surform small bands along the bottom edge, slowly blending them to form the radius of the rail bottom. Each time I shape a ‘down rail’ I am reminded that two of the most significant advances in the evolution of the surfboard are largely unheralded: the ‘backyard revolution’ that came with the shortboard, and the application of the ‘down rail.’ The advent of the flat bottom and ‘down rail’, more than any other single design breakthrough, allowed surfboards to evolve from sluggish displacement hulls into planing hulls. Breakaway edges and flats are some of the most potent spells that the shaper as wizard can bestow upon a surfboard.

It was time now to shape the rails. I turned the blank deck up, weighted it down, and followed the planer as it cut each angled band along the rail. The surfboard suddenly sprang to life. The once blunt slab of rail blossomed into a finely-boned foil, its compound curves fusing to form an organic whole. When both rails were done, I set the planer down and blew the foam dust from the blank. If ever you want to appraise a surfboard as a sculpture, this is the time. In the low sidelights, each band is thrown into crisp relief as they flow from nose to tail, resembling lapstrake planking warping around a curving hull.

It is at this stage of construction that I consider the board to be in its ‘roughed out’ state. The actual design shaping is largely finished, and everything that follows is more or less cleaning up the blank for glassing. ‘Finish work’, as shapers call it, demands a separate set of skills than does imagining and forming the vee and rocker and rails into an efficient surfboard. While the shaper’s craftsmanship shines from an immaculately finished blank, his understanding and control of design components illuminates the ‘sea-worthiness’ of its ribs and keel.

Many shapers now prefer to use computer-controlled shaping machines to generate the bulk of their ‘roughed-out’ blanks. It takes me approximately 30-45 minutes to get a blank to this stage. I have never been able to grasp why a shaper would allow a significant chunk of his shaping fee to be shunted off to a machine – especially when many skilled production shapers are able to ‘rough out’ a typical stock model in far less time than I can.

Those who rely on the shaping machines often grow defensive about using them, claiming that there resides in their surfboards no less ‘soul’ than that shaped by the grooviest backyard hand-shaper. From there, what should be a secular debate quickly degenerates into a psuedo-spiritual dog-pile. A world-famous shaper, and proponent of the machines, once stated that the “shaping machine is a tool, just like a planer, just like a piece of sandpaper and a block, it’s a tool.” I imagine similar fuzzy thinking would no doubt claim that a Xerox machine is the same as a paintbrush.

When the combatants start slinging the word ‘soul’ around, watch out for even sloppier rationalizations. The same shaper further stated that he had “yet to find the soul in pushing plastic around with a planer.” I’ve always believed that this argument is flawed, along with many similar invocations of ‘soul’, because it presumes that ‘soul’ is a commodity that somehow survives the commercial pipeline to bathe the consumer in its pixie dust. But ‘soul’ is non-transferable, if it exists at all – remember that all our surfboards come out of the same oil well.

Therefore, it seems reasonable to state that the only ‘soul’ that matters is the one possessed by the craftsman/artist – is he or she a better person for having created something? Does it lower the blood pressure or prevent them from kicking the dog? By creating with their hands, are they able to sidestep the singularly American neurosis wrought by the hollow religion of consumption? I pay little attention to any nebulous ‘soul’ quotient that may or may not inhabit the surfboards I build. I build them because I love to work with my hands – it keeps me sane in a society that values nihilism over creativity.

The humbug of ‘soul’ has obscured the strongest indictment that can be made against shaping machines: That they sterilize the seedbed of progress. A few years ago I found myself arguing with a veteran of the surfboard industry. Unable to elicit enthusiasm from me on the value of his new shaping machine, he finally lost his temper.

“I’m an engineer, you’re an artist,” he spat, making it clear that he believed artists belonged on the other side of the rabbit-proof fence. “It’s a tool, you hear! It’s perfect, exacting!”

“Yes, I see,” I replied. “But evolution is based on imperfection, on mutation, on the happy accidents and odd little quirks of nature. And surfboards evolve just like living things. Hell, half of the time surfboards improved by accident, through mistakes made in the shaping process. The other half of the time the shaper didn’t hit what he was aiming at, but lucked into hitting a hidden bulls-eye.” I went on to say that because of the increasing value placed on materials over performance, I saw more and more surfboards that aircraft designers would call ‘iron peacocks’ – gorgeous planes that can’t fly.

Surfboards like the one I was shaping for Flippy could never materialize in the cradle of a shaping machine jig. Like all hybrids, it had to evolve in fits and starts, year by year and curve by curve. Original, custom surfboards – the boards we all want to ride, the boards we shapers want to make for our friends – cannot emanate from the inbred eugenics of software and sales demographics.

Normally I take a break after roughing out a board, but as with driving, sometimes you become so absorbed in the journey you don’t want to pull over.

I began blending the rail bands into the last few inches of nose and tail, thinking about some of the boards I have built for my friends. My clientele consists largely of friends and an extended family of repeat customers. What strikes me most about them is the diversity of their surfing lives. Mark Renneker’s fleet of arctic icebreakers rarely sees the sun, while Brian Keaulana’s Makaha quiver is never out of the sun. My friend Jeff Chamberlain’s 12’6” ‘ElectraGlide in Green’ is so massive that he must cart it from spot to spot in a trailer, while Zach Hartley’s pro model shortboard is so compact it fits into the trunk of his ’65 Fairlane.

My train of thought followed these lines for awhile as I worked to blend the transition of the rail bands, painstakingly folding them up into the slight roll of the deck panels. Each stage of finish work telescopes into the next, each tool progressively finer and more exacting than the last. All of the strenuous, noisy work was over, and it was pleasant to float over the emerging shape, gently coaxing an egg-tip softness here, a delicate edge there.

With the planer silent, I could better hear the Hawaiian slack key music on the cassette player, pouring its soothing calm into the cool dark room. I have noticed that the old Hawaiian songs really cosh some of the surfing ‘sourdoughs’ on the back of the neck. It must have been hard to see both places they loved, Hawaii and southern California, ruined before their own eyes. Flippy spoke wistfully of his years at Makaha. He seemed to most remember the diving. Those early pilgrims dove out of necessity, seeking to add valuable protein to a diet of stolen pineapples and canned beans. The horrendous wipeouts suffered by the old-timers were never a problem, he claimed, because they had all spent so much time underwater, plunging down to ear-splitting depths, holding on to ledges upside down and poking their three-prongs into cracks in the reef.

One night we sat on the boat trading diving tales.

“Boy, those Hawaiians sure do love their red fish, I tell you,” said Flippy. “They’ll go down 40 or 60 feet for a little menpachi. Too much trouble now – just give me a peanut butter sandwich and I’m fine.”

Flippy still dove, mostly on his trips out to the Channel Islands. He brought a couple of scuba tanks and rationed his supply of air with the same frugality he did his beloved cache of pudding cups. Each day he meticulously surveyed the tide and wind and swell, hunting for the best time and place to spend his daily allotment of air. Then he would struggle into his thick wetsuit, strap on his tank, and back down the ladder into the water, reaching up as we handed him the battery-powered scooter, which he used to carry him down to the sea floor.

His favorite places to dive were along the edges of large kelp forests. One bright calm day he picked his spot, choosing a drop-off at the western edge of a thick bed of kelp. It was yellowtail country, so I grabbed a speargun and jumped in after him. Freediving, I followed Flippy to the limits of my lungs, watching as he skated between the swaying stalks of kelp, his form fading into the purplish-black depths until only a stream of bubbles remained.

The kelp forest, in clear water and streaked with beams of summer sunshine, must be the most beautiful setting on Earth. Forgetting the yellowtail, I followed the shafts of opalescent sea as they wended through canyons of lolling kelp, transfixed by the watercolor palette and the hypnotic undulation of the forest. Bubbles wobbled up from the bottom – I could picture Flippy, a hundred feet below me, gliding over the silent reef, his eyes from force of habit sweeping over each crevice. The big red abalones were all gone, fished out long ago, but he liked to search for a certain sub-order so rare as to be thought extinct. If he found one, it would make the perfect capstone to his career as an abalone diver.

He took no speargun on his dives, and left the fishing entirely up to us. In the late afternoon, after we had anchored for the night, Matthew and I pulled on our wetsuits and headed off to catch our dinner. On the eve of our departure, we found ourselves anchored in a snug sandy cove. It was getting late, but we dove in and split up. Matthew coasted over the sand flats, looking for halibut, while I took a three-prong and made for patch of reef and kelp near shore. Flippy liked a calico sea bass for his supper. He even stipulated the size – it had to fit exactly on his barbeque. Fish were everywhere, and as the sun set we climbed back aboard, Matthew toting a large halibut and a brace of lobster, and I with the duly prescribed grill-size calico.

Claudia boiled the lobster and sautéed the halibut, while Flippy sealed his fillets in tin foil and baked them in his covered grill. There were baked potatoes, salad, cold bottles of beer and, later, a ration of chilled pudding from Flippy’s private hoard. We sat in the velvety dark, well-fed and content, pausing in conversation to gaze up at the clear night sky. It was the last night of our trip, so I sought to savor every morsel of the happiness I felt. A dozen commercial fishing vessels were scattered across the cove, and from each warmly-lit cabin came the smells of cooking and the tinkle of laughter. Flippy produced a short wave radio, and we had hot tea and listened to a Los Angeles station broadcasting old radio shows from the ‘50s, Jack Benny and a crime drama called “Johnny Dollar.”

Everything – the bright stars overhead, the untouched coastline with its plentiful game, the cheerful greetings from the crews of the other boats, Jack Benny’s wisecracks – all seemed to haul us back into time. It was the easiest thing to imagine we were floating alongside the California of Flippy’s youth, and it dredged up in my mind long-forgotten memories of my childhood in southern California – fragrant chaparral blanketing the empty hills, sleepy Dana Point before the harbor, the coast highway deserted on a foggy morning, the smell of orange blossoms borne on a warm wind.

Then Johnny Dollar dodged a slug and solved the crime, and Flippy switched the radio to the weather band. A computerized voice forecasted 20-25-knot northwest winds for the next day. Flippy, grousing about bashing home in a heavy beam sea, declared we would pull the hook at 5:30 a.m. The enchanted reverie of time warp dissolved as I realized that in little more than 12 hours we would be flung back into the gray ozone muck of the mainland.

I stood in my shaping room looking blankly at the jumble of tools on the shelf. My wandering thoughts sometimes pull me so far from the surfboard that I forget what I was doing. Inspecting the blank for clues, I realized I had moved through several stages in a trance. The deck rolled smoothly into the rails, the bands long since tapered and whittled into roundness. Ah, yes, I had been looking for the small block plane kept especially sharp for finish work. I picked up the plane and slowly shaved the stringer down to deck level, taking care not to shred the surrounding foam.

Then I tilted the board into the crook of the racks so that the rail slanted in profile. I dug through a stack of sanding screen until I found a sheet of stiff new 80-grit. Wrapping it tightly around the rail, I pushed it along in one unbroken pass from nose to tail. Smoothing the rails with sanding screen is perhaps the most satisfying of all the shaping stages. The hands feel the tapering flow through the thin abrasive; foam dust seeps through the screen as it glides over the soft foam, each pass offering less resistance until it seems to caress the rail rather than abrade it.

However, at some point in the rail blending it is easy to stray into over-shaping – you are dithering instead of adding anything meaningful to the design. After ensuring that the rails matched each other, I turned the board over and sanded smooth the bottom with a block of high-density foam. Next, I folded a small square of pliant screen over the radius of the rail bottom, and pushed it delicately toward the nose and back again, until the edge twisted evenly from hard to soft. I miss seeing hard edges on surfboards. They have largely disappeared from contemporary design, as most surfers now seem to prefer surfboards with neutral characteristics. But a firm tucked-under edge can make even the bulkiest surfboard feel crisp and fast, and would help drag the 37-year-old fuselage of Flippy’s board into the modern, lickety-split jet age.

Now the offramp loomed in the distance and the wandering road of the day’s work coasted towards the exit. A flick of screen here and a pat of sandpaper there, and Flippy’s surfboard was finished.

I began measuring out the setting for a fin box, but then decided it would be best to go with a glassed-on fin. You have to watch these blokes who started surfing in the days of wooden boards – give them a chance and they’ll bolt the fin right to the very edge of the tailblock. I marked dots on the stringer for one of my gun fin templates, along with the board’s measurements. Then I took a soft blunt pencil and inscribed

“11’0” for Flippy”

on the foam below the stringer, and signed my name above it.

I always finish a day’s shaping feeling better than when I started. Not once have those hours spent immersed in cutting and planing and sanding failed to lift my mood. For me, an unrepentant introvert, shaping has come to largely replace surfing as my primary wellspring of serenity. Everything I sought as a young surfer – challenge, solitude, a sanctuary for quiet reflection, a creative outlet – I now find more readily in the discipline of each day drawing and cutting out a new surfboard.

I laid Flippy’s new board against the wall and surveyed each part of its design: the arc of the nose curve that had been sired by Kivlin, Quigg, and Brewer; the widepoint that peaked with the apex of bottom rocker and thickness; the mild taper of the waist as it streaked down into the soft pintail. Its shape was a new thing, and yet every bend, every race of curve, could likely be traced back 1500 years to the koa forests of Hawaii.

I had set out to make some notes while engaged in the shaping process, to follow the meandering road wherever it led. Shuffling through them, I see that the past, the present, and the future all beam through the prism of the man it was made for. Perhaps that is how it should be.

Once upon a time, to look into a shaping room was to peer into an enchanted and mysterious grotto in which a priestly caste forged our swords. As a gremmie, I would have stepped over Larry Bertlemann or Jeff Hakman to catch a glimpse of Dick Brewer or Tom Parrish or Sam Hawk. Today, the mystery and magic possessed by these and other Merlins seem to have vanished. Blanks are dumped by the truckload at the foot of overbooked shaping machines; the router blades whine along their programmed tracks, and the finished blanks stream into enormous glass shops like sardines into a cannery.

I know many shapers who have burned out after decades of building surfboards. I have made a careful study of the disease, and have concluded that each shaper must carefully choose amodus operandi that best suits his temperament. The choices span an incredibly wide range for such a narrow field: From Bob Simmons, who reputedly would only make surfboards for people he liked, to Those-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named, shapers who make Faustian deals with the molded pop-out barons. Somewhere in between lies a happy nook that can allow each craftsman, if he can resist the oncogenes leading to self-destructive growth, to sustain a long and passionate love affair with surfboards. All our surfboards may come out of the same oil well, but our passion for the surfboards we have ridden in the past, and our excitement over surfboards we will ride in the future, must always bubble up from the imaginations of craftsmen who seek to maintain an equilibrium that balances work and creativity.

Flippy’s board went off to the glasser to be laid up, sanded and polished. A few weeks later I was in the middle of shaping a Fish, an antidote for a friend stricken with longboard malaise, when a fax scrolled into the tray. It was from Flippy.

“Fan-dam-tastic!” read the note. “My ship has come in!”

Smiling, I clipped the fax to the sheaf of notes I had made, put a new cassette into the player, and waded back into the calm, silent pool of my craft.